Read this article in the limited edition print version: order a copy here.

Every Sunday, a Passionist church at the centre of Paris welcomes a congregation through its doors. For the most part, it’s a crowd of English-speaking immigrants, travelling inwards from dispersed homes. They meet together for Mass, and then the church does it again: five times, in fact, performing the liturgy over and again for five different audiences throughout the day, the house packed each time.

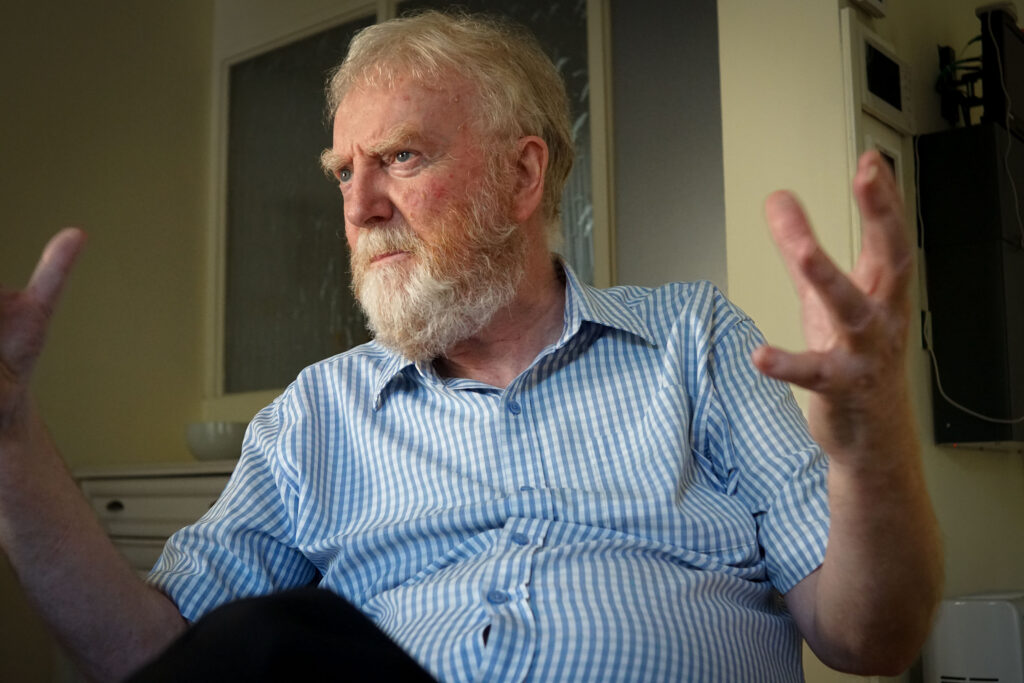

At the heart of this operation is one Fr Martin Coffey, who we meet outside St Joseph’s Church on Avenue Hoche in scorching sunlight. Aside from a joking discomfort with the heat, Martin seems at ease here; he has the ready adaptability of a man who’s made his home in a variety of contexts and countries.

St Joseph’s is in a truly extraordinary location; there has been a building here, in spitting distance of the Arc de Triomphe, since the 19th Century. With the original building razed in the 1980s, the new church sits semi-submerged beneath a co-owned tower block, hiding in plain sight. We also can’t avoid the fact that, well, we’re in Paris; a rather surprising place to fall under St Patrick’s Province’s purview. As we chat with Martin, we unpick the two journeys that brought us here—Martin’s own journey from his childhood in Ireland, and the Order’s connection to the English-speaking diaspora in Paris—and get a sense of the character of both.

The Enthusiast

The high Parisian heat probably explains why Martin’s given into a priestly cliché: greeting us in his sandals.

It’s true that in some respects, Martin fits the profile of who you might picture in a religious order. For a start, he describes faith as something he learned “by osmosis”, growing up in Ireland in the late 1960s—“an atmosphere of religious saturation. It was the air you breathed.”

There was nothing unthinking about Martin’s acceptance of that faith, though. In fact, “unthinking” is about as foreign a word as you could conjure to describe Martin Coffey. “I was very definite that I didn’t want to be a priest,” he’ll tell us in no short order. “There was nothing about priests that I identified with. Our family had no real close relationship with any clergy; they were always a bit distant, up at the altar, doing mass.”

In his family, in fact, he experienced the push-and-pull of religious authority up close: hearing one thing from the local priest and then hearing it unceremoniously analysed by his mother and sisters around the dinner table.

Even more unusually, his brother—a radical socialist, and an atheist to this day—gave him a wider social awareness than his peers might have had. “After my brother left home, we still received a regular magazine from the Viet Cong—with photographs of the atrocities committed by the Americans—every couple of weeks. We were instinctively sympathetic to the Vietnamese, but this magazine took us further.” Religious saturation there may have been, but already, you could hardly describe his upbringing as black-and-white.

“There is no place I’ve ever been where I did not feel fully and totally alive and engaged.”

“It’s not that I never questioned it,” he agrees, “but I never had a serious crisis of faith. It was more about asking cosmological questions; what does it really mean? Why is there something rather than nothing? The challenge is to get from the words into something that makes it real.”

Reality took the form of the Christian brothers in the neighbourhood. Where the priests were distant figures at the altar, the brothers were in the schoolyard, playing football. “As a kid, being in that environment of friendliness and after-school activities, I admired that; I wondered if I could do that. They were teaching us, preparing us for our future, for exams; they were encouraging and pushing us. I could see they were doing something really good and important.”

It’s hard not to conclude that Martin somehow inhabited a time of history that was tailor-made for his personality. Education, University, and widened possibilities were exploding for ordinary people growing up in Ireland: “We had that conviction that the whole world was at our feet.” When he did begin to explore religious life, in the early 70s, it was a time where the church was still opening up in the wake of Vatican II.

“Previously, as a young Passionist, you immediately went into this secluded, silent, separate world. We were the first not to do that; we had a gradual introduction. I was always given space, or scope, to say or think what I wanted,” he enthuses. “We were very lucky.” Martin, and others his age, were allowed to live in the religious community for a while before making any grand commitment. The community, for its part, was attempting to reverse a trend where young men took their vows and quit not long after. “The idea was: come, see, make up your mind, but make an informed decision.”

Martin credits the community with an attitude of openness, welcome and trust. Clearly, he responded gregariously to this approach, settling into the journey that would shortly become his life—with no regrets to speak of. It’s hard to disagree with the man’s description of himself as an enthusiast. “There is no place I’ve ever been where I did not feel fully and totally alive and engaged. That’s when I was 25, 35, 45, 55, 65.. Still the same today.”

The Transformer

That brings us to today, then, with Martin leading a church in Paris. If he seems surprised by this development then he certainly doesn’t show it.

The origins of the Passionist presence in Paris go back to the 1860s; it was founded in a boom-time of sorts for the church, an accommodating ebb in French political history. Allowing for the somewhat 19th Century quirks of Protestant rivalry and moral panic, I’d say the heart behind the project was not so different from today: to provide a spiritual home for English-speaking Catholics in the capital. It existed as much for Catholic families from the colonies as for the English or Irish themselves.

The times have changed—repeatedly—but the through-line is that internationality, and perhaps the idea of refuge, too. Not in the sense of hiding things away, but rather the need to give sustenance to people whose day-to-day existence is under constant pressure. And in Paris—the capital of laïcité—that pressure and constant drain doesn’t necessarily come from the place you expect. “There are very few spaces, few publications, few organisations for any socially-conscious, left-leaning Catholics here,” Martin tells us. “The left lost heart, and moved away.” There is, instead, a “restorationist, monarchist, narrow right-wing Catholic section of the French public here. They’re very alive, very active, and intending to take power.”

Over time, the Passionist congregation became a refuge from that vision of the church; in the process, it became the only remaining English-speaking Catholic centre in the city. Those looking for it often hail from other parts of the world, places where Liberation Theology blooms and working class concerns take precedence. “The vast majority of our parishioners are domestic workers; cleaners, those who look after people’s children, and so on. They’re Filipinos, Sri Lankans, people from different African nations. They have a relatively hard life. The hospitality we offer people here is very important; we say, ‘This is a place where you feel at home’.”

Despite his status as an intellectual—his explanation that his pastoral ministry “has always been one or two steps removed from the coalface”—Martin’s concern for the people in his displaced parish has a visible warmth.

“It’s an experience I’ve had again and again,” Martin explains: “A great sense that there is no-one I meet, there is no-one in this church, there is no-one in this community… who is not carrying some cross; or is not enduring some kind of trial, or struggle—about which we know absolutely nothing.”

The weight of his words is palpable. “And therefore keep that in mind always; in how you speak to people, in how you make space for people, in how you respond to their needs; that you only see the surface. Just know that beneath the surface in every human being, there is a broken heart, there is a painful experience, there is a frightening future; whatever it is. And the church, the community of Christ, is embracing, welcoming, helping, delivering, saving, that situation.”

Refuge, though, is not an end goal in Martin’s mind; more like the necessary groundwork. “I think we are moving out of a religion of consolation and comfort,” he muses later. “That was the dominant spirituality; we turn to God in times of need… we know that God is good, and he has gone to prepare a place for us… in other words, grin and bear it, but there are better days coming.

“Our Christian faith is actually a call to get engaged. Part of the Gospel is the transformation of the world into the Kingdom of God. If we listen to the Gospel, if we participate in the liturgy, if we have the Spirit of God in us, then that’s what the Spirit is doing in us: it’s turning us into those who will transform the world into the Kingdom of God, here and now.”

“There is no-one I meet who is not carrying some cross.”

What does that potential future look like—here, in this Province? “Everybody knows that the future of the planet depends on us, in the West, discovering the need to reduce our consumption, to reduce our possessiveness, our need to have, and so on. Now, there is no possibility of that happening on a political level without a massive, catastrophic revolution. So what kind of contribution can we make towards that goal, instead? Maybe it will be some kind of—let’s call it a spiritual, anthropological, cosmological insight, that will help people to make that shift.

“Otherwise, we’re going nowhere. We’re not making any impact on the climate for as long as we want to keep all the things we have, and the things we haven’t got yet.” For my part, I can’t avoid asking—how does someone not lose heart? Where are the ‘signs of hope’, as a Passionist might put it?

“We are not naive,” Martin says thoughtfully. “The Passionist thing is this: our saviour is the crucified one. When the great transformer came, the great saviour, the great prophet: we killed him. That just hits me in the face that whatever engagement we undertake, it’s going to be uphill. And it’s not going to just ‘fall into place’. And we’re not going to be able, very easily, to convince people of it. I believe in it, of course, I believe in the Christian vision of nonviolence, forgiveness and service, and love. These are the things that everybody is longing for.

“But we have to keep at it. We have to keep at it. And we have to be prepared, somehow, to be crucified for it. Self-sacrificing love, in the conditions and circumstances we are, with the faith that that love will bear fruit in new life. Salvation comes through that self-sacrificing love.”

Does he think that sounds a bit fatalistic?

“Not at all! This is the way we put our brick in the wall. The completion of the wall, that’s not our task. Our task is to make our contribution. Not losing heart—that comes from collaboration, opening up, working with others, contributing your gift: which is not every gift.”

The Stargazer

It’s a too-rare thing to encounter a person in the later stages of their life, heavily intellectual, and yet deeply compassionate, and above all genuinely joyful in demeanour. It’s not something you could imitate unless it came from a fully realised inner peacefulness. Martin, to his credit, seems entirely at ease with who he is, and his role in relationships: “We always need people who are able to stand back, look at things from a distance. Individual enthusiasm wanes if it’s not supported by some kind of theory, or vision.”

This takes us back to Martin’s persona as the enthusiast. I get the impression of a man who carries an undimmed spirit with him, someone who urges others onwards—animated by a genuine belief in people, despite a lifetime of experience of humanity’s foibles. I can see his point: many of us could use that enthusiasm from time to time.

“We’re unlikely to encounter anything as complex, as wonderful, as amazing, as the human mind,” he says, citing the author Marilyn Robinson as his inspiration here. As incredible as the sights we discover in the sky might be, “we won’t find a reflecting, loving, forgiving star. And that’s the God presence in us. And actually only we, in a sense, can experience the joy of discovering all those stars; and therefore those stars only really shine for us. We’re the only ones who can appreciate them shining.”

Here in Paris, Martin seems awed by the possibilities in those five full Masses’ worth of people, making their contributions in the city. “There’s so much goodwill out there. There’s already a lot of volunteering, but the potential is enormous.”

What could that potential look like? “Everybody has grown up with a system where there is the Parish priest, and he is the driver, he is the planner; but to be able to tap the energy, the creativity, the possibilities in our congregation—it’s a tremendous challenge. To direct those latent energies towards, for example, our migrants, and the people on the street—backed up by a strong spirituality of commitment and encouragement. That’s the kind of thing that I’m trying to grope towards in this parish.”

As might be befitting, we leave St Joseph’s Church deep in thought. The sun beats down, and Avenue Hoche’s towering architecture casts long shadows onto the pavement. The faith of others can be an inspiring thing, but faith in humanity, when you really see it—that’s contagious.

Related Stories

Inner State: Passionist Life in North Belfast

North Belfast is a community that has seen immense trauma over the past century – defined by political forces beyond its control.

May 30 2024

Positive Faith present a World Aids Day service, ‘The Reason for Hope’

Reflections, music and scripture as well as opportunities for sharing on this World Aids Day online service.

Dec 01 2023

Dust to Dust: Passionist Life in Haiti

In Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Fr Rick Frechette has been the cornerstone of a Passionist community all giving their lives for the beleaguered nation.

Oct 31 2023