A Brief History of the Passionists, from St Paul of the Cross to Today

“The service of God does not require good words and good desires, but efficient workmanship, fervour and courage”

St Paul of the Cross

Paul of the Cross: Early Inspiration and the Founding Spirit of the Passionists

Saint Paul of the Cross was born Paul Francis Danei in 1694. He founded the Congregation of the Passion in 1720, in northern Italy. He had a profound mystical experience, which prompted him to embark on a forty day retreat in a single room attached to a church (actually it was a sacristy). Paul wrote down his mystical experiences and is regarded as one of the foremost mystics of his century.

After the retreat, he felt God was calling him to start an Order, so he gathered companions to share his life. He had visions where he saw himself wearing a black robe (the clothing of the poor at the time) and of what is now the Passionist sign. The original name for the Order was ‘The Poor of Jesus’. They lived in a very real voluntary poverty such that all the early brothers left, apart from Paul’s blood brother Jean Baptist, as it was too rigorous and many became ill. Paul’s intense spiritual experience led him to emphasise strongly the contemplative part of the life of his Order, which, being founded in the centuries following St Ignatius’ founding of the Jesuits, were to be a form of ‘active contemplative’, expressed as a type of semi-monastic life.

At a later point, following a spiritual revelation, Paul was inspired make the Passion the centre of the charism and spirituality of his new community, hence the official name ‘The Congregation of the Passion of Jesus Christ’. Paul felt that the Passion was being forgotten. In fact there was plenty of devotional literature and practices relating to the Passion in 18th Century Italy, but Paul believed the Passion was not being understood correctly. He saw the Passion as ‘the greatest, most overwhelming, work of God’s love’. For Paul the Passion was a revelation of the love of God: it was not about placating an angry God, or about guilt, or even in a sense about suffering, except in as much as the suffering of one who is loved will lead to the one who loves to compassion for the sufferer, that is, suffering-with. This overwhelming sense of the love of God is very much in common with all profound and genuine mystical experiences.

The Passion of Jesus is central to Passionist life such that each Passionist takes an extra vow, (a fourth, or first vow) to ‘keep alive the memory of the Passion’. This ‘Memoria Passionis’ is at the heart of Passionist life, charism and spirituality. Everything is ordered towards making that mission possible, remembering that by reminding people of the Passion, Paul of the Cross had the intention of reminding people of the overwhelming love of God. This was manifested by a real compassion and love that people felt was present in Paul. It was also manifested very obviously in his preaching of the passion, and teaching meditation on the Passion. At that time, it was generally felt that meditation was for priests and religious, so to teach lay people in this way was innovative. Part of the continuing Passionist commitment to poverty was also a commitment to the poor.

The early Passionist communities were in the part of Italy just north of Rome. The first Passionist community was on an island, Monte Argentario, because of its poverty, silence and solitude. Later, Paul realised he needed to be in a less isolated place in order to be able to carry out the mission God had given him. So they moved to a place called ‘the marema’, a marshy land, full of mosquitoes and disease, a place which because of the conditions and the poverty of the people was avoided by the majority of clergy and religious. In that sense it was a place without much presence of the Church, without much religious practice or knowledge. It was to such uneducated and impoverished people that Paul went, to teach them of God’s love through the Passion. He would also help in any way necessary in the pastoral work in the locality, for example teaching catechism. In this way, Paul and the early Passionists carried out a form of mission in their own country.

Paul developed a typically Passionist style of preaching, and a practice of travelling within the area and wider to give ‘missions’. He had to struggle to get his Rule accepted by the Church, with considerable modifications. Although after 20 years of trying to start an Order, only Paul and his brother had persisted, by the time of his death in 1775, his congregation was flourishing.

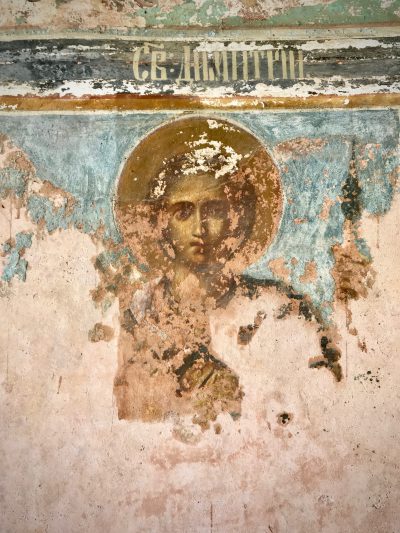

The Passionists did not grow beyond Italy (apart from a brief attempt to start a presence in Bulgaria) until the 19th Century. However, in his early mystical experiences, Paul had been inspired to pray for England and shortly before his death, he had a vision of his ‘children’ in England. So in 1841 Dominic Barberi arrived with a few companions, via a foundation in what is now Belgium.

The Passionists in Britain

Dominic Barberi had already been involved in ecumenical relations with Anglicans and other Protestants before arriving in England, mainly through exchanging letters. The spirit was of what we would call today fraternal dialogue, the mutual recognition of the good will and Christian faith of the other ‘side’. This was unusual at the time. The ecumenical outreach of the Passionists in England increased through especially Ignatius Spencer, who travelled around Britain and neighbouring countries promoting prayer for Christian unity, and particularly his idea of a week of prayer which became the fore-runner of the week of prayer for Christian unity. Both Dominic and Ignatius had positive relationships with the Oxford Movement in the Church of England, which led in part to Dominic receiving the leader of that movement, John Henry Newman, later Cardinal Newman, into the Catholic Church. Indeed, Passionists of the era still prayed for ‘the conversion of England’.

Another factor in Newman’s becoming a Catholic was the commitment of the Passionists among others to care for the poor of the great Victorian city slums. After the potato famine started in Ireland in 1847, there was a massive flow of Irish Catholics into the poorest parts of cities like Liverpool, Birmingham and London. There, they suffered from the worst of all the deprivations associated with that life: hunger and starvation, enormous overcrowding, exploitation and disease, and more. Passionists including Dominic, Ignatius, and the Cross and Passion Sisters (founded to work in the Lancashire industrial towns among poor girls), went among the poor to help care for the sick with diseases like cholera and TB. A number of Passionists in fact died from such diseases. This was a real sacrifice, notably for someone like Ignatius (formerly George) Spencer, coming as he did from the enormously wealthy Spencer family (the family of Diana Spencer). Their commitment and sacrifice was a real witness, both to fellow Catholics as well as others, for example, the members of the Oxford Movement.

After the inevitable initial trials, the Passionist Congregation, as well as the Cross and Passion Sisters, grew in number and became firmly established in England, Scotland and then Ireland. They grew in numbers sufficiently that two separate Provinces were established, St Joseph’s Province for England and Wales, and St Patrick’s for Scotland and Ireland (Ireland was under British rule at the time). Almost every Catholic in these islands would have been familiar with Passionist parish missions in the first half of the 20th Century. Passionists travelled the length and breadth of the country giving parish missions. The mission sermons were always dramatic, often full of ‘fire and brimstone’, to prepare the people to hear of the love and mercy of God later in the week perhaps, and experience it in the confessional, with confessions being a standard part of Passionist mission practice. In the period before the Council, starting in the USA, there was a move in the Congregation towards retreat house work, as a new way of manifesting the understanding of the Passionist charism as one of ‘preaching the Passion’.

The Impact of Vatican Two

The Council called for and initiated a thorough and deep renewal and changes in Catholic Religious Orders, in response to the changing times and a changing world and society. In the Passionists, as with other Orders, this has led to a substantial change. In common with nearly all Religious Orders in the ‘west’, Passionist numbers in this part of the world have declined greatly, while the Order has spread and grown in what is known as the ‘global south’. This decline in the west has been interpreted in many different ways. I do not want to go into this debate here. There is no doubt that many left their places in the Church either because it had changed too much or because it had not changed enough. That there were substantial changes is also undoubted.

In 1980, the Passionist Congregation adopted a new Constitution to replace the Rule. This Constitution had been in development since 1968 at least. It has been said that it represents a shift away from a Rule that was culturally specific with many specific practical instructions, to a Constitution that enumerates the principles but leaves concrete implementation to local decision making. But there is perhaps more to it than that. In addition, Passionist spirituality made an explicit connection: Paul of the Cross had talked about ‘seeing the cross of Christ on the forehead of the poor’. The new Passionist Constitutions speak of being in solidarity with ‘the crucified of today’, and say that ‘the cross of Christ continues in history’. The combination of the move to ‘principles’ with the call to identify with the crucified ones as well as the Crucified One, has resulted in a variety of responses.

One response in England was to continue running the Parishes that Religious had been obliged by the Bishops of the time to take on if they wanted to enter a Diocese. Another was to move towards more retreat house work. Both of these in different ways continued trends or practices from before the Council. The third, present in England, was a move to live alongside ‘the crucified of today’, among the poor in the ‘more neglected areas’ (as Paul had described the marema area). In England this was called the ‘Inner City Mission’. This was described as an attempt to ‘stand at the foot of the cross’ of the poor and crucified, as a good place to meditate on or contemplate the passion, as all Passionists have been taught to do since the days of Paul of the Cross. This, as always, is intended to move on to a ‘sharing of the fruits of that meditation’, having been evangelised by the crucified.

Passionists in Britain since Vatican Two

In England and Wales, St Joseph’s Province had been focussed on the parish missions, as well as running a few parishes in places like Highgate. After the Vatican Council, there was a decline in Parish missions but retreat work expanded. By the 1970’s, there were 3 retreat houses: Minsteracres near Newcastle, St Non’s on the west Wales coast, and Myddleton Lodge youth retreat centre in Ilkley, Yorkshire. From the early 1970’s, small communities of the Inner City Mission presence began, first in Toxteth, Liverpool, then in Islington / Hackney, London. In Liverpool the focus was on engagement in the local community of the ‘Granby triangle’, and in London the focus was on the workplace and trades unions, through taking low paid manual work jobs such as street sweeper or hospital kitchen porter. St Joseph’s Province mission presence and ministry in Sweden continued through this period, helping to build up a small but growing and youthful, mainly immigrant, church.

In 1996, due to falling numbers and ageing membership, the Province made plans to ‘hand on’ existing institutional works, in order to be free to ‘reach out in new ways to the crucified of today’. The current situation (in 2015) is of a Passionist presence in England and Wales very much in flux. Most of the parishes have been ‘handed on’ to the relevant Dioceses. Highgate has been ‘handed on’ to an international community that is not a responsibility of St Joseph’s Province, but supervised directly by the Passionist General in Rome. St Non’s retreat house is run by Mercy Sisters, and Minsteracres is an independent charity with lay leadership, although still retaining Passionist identity and members, including one member of the St Joseph’s Province, two from other Provinces, and two Cross and Passion Sisters, as well as substantial lay participation in the form of community members, paid staff and volunteers. The Province retains a parish in Herne Bay in Kent, where a number of the elderly men live in the community house. There are still individuals maintaining an inner city presence in Newcastle and Liverpool, a Passionist ministering in a parish in Scotland, and another living in Otley, Yorkshire, ministering through psychotherapy and retreat giving. The two youngest members by far live in Sparkhill, inner city Birmingham, continuing the Inner City presence in an overwhelmingly Muslim and substantially Pakistani area. They comprise two-thirds of the Province leadership and host six destitute male refugees in their house.

As can be seen from the above brief survey of the Province, while the declining numbers (currently 20) and the increasing age profile have continued, there has also been a proportionate shift towards Inner City presence, towards putting into practice the understanding that the passion of Christ continues in history in the ‘crucified of today’, now also extended as Pope Francis has said to our sister earth. This inner city mission can be seen very much in continuity with the Founder’s practice of local mission in neglected areas, reaching out to the poor and sharing their poverty.

While the process of change, declining numbers and ageing has been at times painful, we still hope that the process of transformation and renewal is continuing. We see in this process the reality of the paschal mystery, of death and resurrection, of endings and beginnings, of dying and coming to new life. Currently, we are working towards a greater unity and a more specific and coherent common understanding of what the ‘reaching out in new ways to the crucified of today’ entails, hopeful that, to quote an African saying, “the longer the stew cooks, the richer the flavour”. To this end, we are working on a number of aspects. One is the founding and now growth of the ‘Community of the Passion’ a Passionist ecclesial (ie mostly lay) movement: another is a process of clarifying our specific Province identity: a third prioritising and adapting the process for joining: fourth, raising our profile and that of our ministry via our presence on the internet and social media, along with other ways: a fifth is to develop a range of partnerships with organisations who will be ‘Passionist Partners’, part of a wider Passionist movement.

All these recent developments are still very much a work in progress. It is a task we believe in hope that we have the creativity and resources to carry through, with the help of God, the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and the passionate love that led Jesus on the way of the Cross, and on to the Resurrection.

Related Stories

Inner State: Passionist Life in North Belfast

North Belfast is a community that has seen immense trauma over the past century – defined by political forces beyond its control.

May 30 2024

To Illumine the Mind: the Catholic diaspora in Paris

In Paris, Martin Coffey leads a church overflowing with working class immigrants. The picture of religion in France, he tells us, is not what you think.

Mar 01 2024

Positive Faith present a World Aids Day service, ‘The Reason for Hope’

Reflections, music and scripture as well as opportunities for sharing on this World Aids Day online service.

Dec 01 2023